Parents Are Cutting Off Their Opioid-Addicted Kids — and It’s the Toughest Decision of Their Lives

Kim Humphrey was sitting in a sea of chairs, surrounded by about 40 people he had never met, when the Phoenix police officer finally realized what a train wreck his life was.

He didn’t want to talk about it. Especially to a bunch of strangers. But his wife, Michelle, had researched addiction support groups online, found one at a recovery center across town, and dragged him here all the same. And now, as Kim stewed silently in his seat, mentally rehashing the made-for-TV movie he found himself in, he had a moment of clarity.

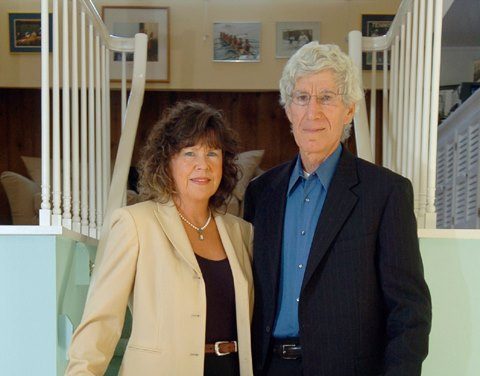

Kim isn’t an addict, but like everyone else in the room, drug and alcohol abuse had sunk its barbs into his kids, and that was robbing him of his health, sanity, and nearly every penny he had. For close to a decade, he and Michelle had shuffled their two sons in and out of rehab centers and hospitals. They paid for cars, medical bills, and legal fees. They handed their sons cash for food, gas, and clothes, and when they realized it all went toward drugs, they tried giving them gift cards instead. (It turns out, thanks to a grocery store’s gift card redemption machine, those could be turned into drug money too.)

In some ways, they had been lucky. Both of their sons were alive, and as a public employee, Kim’s health insurance had saved them thousands in medical costs. All told, the couple still spent more than $50,000 in a futile attempt to save their kids from addiction, he estimates.

The emotional costs were even more staggering. By the time Kim made it to that first support group, the stress of wondering where his kids were, what they were doing, and whether it would end up killing them was so overwhelming, he’d taken a leave of absence from work. He was too depressed to make it into the office, he says. Some mornings, he was too depressed to get out of bed.

“I felt like, as a guy, a cop, a dad, that I should be able to solve this,” Kim, 57, says. “We begged, we cajoled, we tried everything we could to get them help. And everything backfired.”

Money struggles are a common theme in addiction stories. Drug abuse eschews logic; rent money and retirement savings don’t often top an addict’s list of priorities. As a result, many parents, like the Humphreys, foot the bill for every debt their child neglects—on top of every recovery strategy (rehab, outpatient counseling, therapy) they can throw their paychecks at.

Kim met some of these people at his first meeting, and when he came back the next week and the week after that, he met still more. He got to know their stories intimately: parents who spent hundreds of thousands of dollars, emptied out their 401(k)s, and declared bankruptcy on account of a child’s addiction. A mother who had lost her home; a father who had replaced his daughter’s car eight different times. A couple who couldn’t bear to kick their son out of the house but, because he’d stolen so much of their money and disrupted so much of their lives, had resorted to letting him stay in their garage—and feeding him meals through a doggy door.

The meetings were hosted by Parents of Addicted Loved Ones (PAL), a growing network of faith-based support groups sprouting up across the country. Kim says it saved his family.

For years, he and Michelle had wrestled with a question that plagues every family of an adult addict. Should we cut off our kid?

Now they had an answer.

For all the bleak public health reports, for all the PSAs, for all the fist-pounding, change-promising, bipartisan-haranguing stump speeches, the magnitude of America’s addiction problem is still remarkably hard to comprehend.

At last count, more than 2 million Americans were addicted to heroin or prescription opioids, the umbrella term for painkillers like morphine, codeine, and oxycodone. More than 70,000 people died from a drug overdose last year, according to federal estimates, prompting the Department of Health and Human Services to declare a public health emergency. Owing in part to the spike in overdose deaths, for the first time in decades, the American life expectancy is declining.